Overview

TLS (for Transport Layer Security) is the successor of the now insecure SSL protocol. It sits on top of TCP (usually) to provide secrecy (encryption) and prevent tampering (signature) of identities and data. It uses asymmetric ciphering based on key/certificate pairs to exchange symmetric session keys, no manual exchange of initial secrets is required.

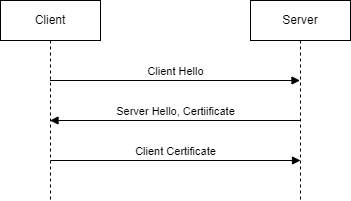

In its mutual form (mTLS), it also provides client authentication using a client key/certificate pair.

Lab

To illustrate how TLS works and where it can fail, we will setup a server and a client using openssl. It’s the only tool you need to manipulate certificates, debug a connection, and much more. It should already be available on any linux distribution, and there are some ports for other OSes too (but for Windows, I’d recommend using WSL to use the linux implementation).

Certificates and trust

TLS is based on asymmetric ciphering, which means that it uses a private key (usually called the key) and a public key (the certificate). The public key can encrypt data and verify signatures, the private key is required to decrypt and generate a signature. This means that the client can encrypt, the server will decrypt, sign, and the client will verify the signature.

To start such a conversation with a given server, you will have to trust its public key first. In order to be actually manageable, you don’t really have to trust each server individually. Just like in real life you don’t know every single person but you trust the company who delivered their badge or the government who issued their ID, in the server world you will trust the Certificate Authorities (CA) who issue certificates to the servers.

The server public key will be signed by a CA and this signature will be contained inside the server certificate. A client will be able to verify the signature using the CA public key. The CA public key itself will usually be signed by another CA and so on, until we reach the root CA (the one at the top of the chain), which will be self signed. You have to trust at least one CA of the chain, usually the root CA. Your OS has a trust store which contains the most common public CAs, on ubuntu for example they will be store in /etc/ssl/certs. This system trust store is regularly updated and contains the most common CAs.

Let’s check with google

openssl s_client -connect google.com:443 <<< "Q"

This little command will open a TLS connection to google.com on port 443. The <<< "Q" at the end is to close the connection right after it’s been established, otherwise you’d have to Ctrl+C. The output contains this information:

Certificate chain

0 s:CN = *.google.com

i:C = US, O = Google Trust Services LLC, CN = GTS CA 1C3

1 s:C = US, O = Google Trust Services LLC, CN = GTS CA 1C3

i:C = US, O = Google Trust Services LLC, CN = GTS Root R1

2 s:C = US, O = Google Trust Services LLC, CN = GTS Root R1

i:C = BE, O = GlobalSign nv-sa, OU = Root CA, CN = GlobalSign Root CA

Here we can see the chain of certificates, the root being GlobalSign Root CA, then 2 intermediate CA ( GTS Root R1 and GTS CA 1C3), then finally the server certificate (*.google.com). If we check in our trust store using the openssl x509 -text -noout -in /etc/ssl/certs/GlobalSign_Root_CA.pem command , we will find the GlobalSign Root CA, so our browsers and most tools will be able to verify Google’s chain of certificate signature. You’ll notice that the Issuer is the same as the Subject, this is what we call a self signed certificate.

Certificate:

Data:

Version: 3 (0x2)

Serial Number:

04:00:00:00:00:01:15:4b:5a:c3:94

Signature Algorithm: sha1WithRSAEncryption

Issuer: C = BE, O = GlobalSign nv-sa, OU = Root CA, CN = GlobalSign Root CA

Validity

Not Before: Sep 1 12:00:00 1998 GMT

Not After : Jan 28 12:00:00 2028 GMT

Subject: C = BE, O = GlobalSign nv-sa, OU = Root CA, CN = GlobalSign Root CA

Subject Public Key Info:

Public Key Algorithm: rsaEncryption

RSA Public-Key: (2048 bit)

Modulus:

00:da:0e:e6:99:8d:ce:a3:e3:4f:8a:7e:fb:f1:8b:

83:25:6b:ea:48:1f:f1:2a:b0:b9:95:11:04:bd:f0:

63:d1:e2:67:66:cf:1c:dd:cf:1b:48:2b:ee:8d:89:

8e:9a:af:29:80:65:ab:e9:c7:2d:12:cb:ab:1c:4c:

70:07:a1:3d:0a:30:cd:15:8d:4f:f8:dd:d4:8c:50:

15:1c:ef:50:ee:c4:2e:f7:fc:e9:52:f2:91:7d:e0:

6d:d5:35:30:8e:5e:43:73:f2:41:e9:d5:6a:e3:b2:

89:3a:56:39:38:6f:06:3c:88:69:5b:2a:4d:c5:a7:

54:b8:6c:89:cc:9b:f9:3c:ca:e5:fd:89:f5:12:3c:

92:78:96:d6:dc:74:6e:93:44:61:d1:8d:c7:46:b2:

75:0e:86:e8:19:8a:d5:6d:6c:d5:78:16:95:a2:e9:

c8:0a:38:eb:f2:24:13:4f:73:54:93:13:85:3a:1b:

bc:1e:34:b5:8b:05:8c:b9:77:8b:b1:db:1f:20:91:

ab:09:53:6e:90:ce:7b:37:74:b9:70:47:91:22:51:

63:16:79:ae:b1:ae:41:26:08:c8:19:2b:d1:46:aa:

48:d6:64:2a:d7:83:34:ff:2c:2a:c1:6c:19:43:4a:

07:85:e7:d3:7c:f6:21:68:ef:ea:f2:52:9f:7f:93:

90:cf

Exponent: 65537 (0x10001)

X509v3 extensions:

X509v3 Key Usage: critical

Certificate Sign, CRL Sign

X509v3 Basic Constraints: critical

CA:TRUE

X509v3 Subject Key Identifier:

60:7B:66:1A:45:0D:97:CA:89:50:2F:7D:04:CD:34:A8:FF:FC:FD:4B

Signature Algorithm: sha1WithRSAEncryption

d6:73:e7:7c:4f:76:d0:8d:bf:ec:ba:a2:be:34:c5:28:32:b5:

7c:fc:6c:9c:2c:2b:bd:09:9e:53:bf:6b:5e:aa:11:48:b6:e5:

08:a3:b3:ca:3d:61:4d:d3:46:09:b3:3e:c3:a0:e3:63:55:1b:

f2:ba:ef:ad:39:e1:43:b9:38:a3:e6:2f:8a:26:3b:ef:a0:50:

56:f9:c6:0a:fd:38:cd:c4:0b:70:51:94:97:98:04:df:c3:5f:

94:d5:15:c9:14:41:9c:c4:5d:75:64:15:0d:ff:55:30:ec:86:

8f:ff:0d:ef:2c:b9:63:46:f6:aa:fc:df:bc:69:fd:2e:12:48:

64:9a:e0:95:f0:a6:ef:29:8f:01:b1:15:b5:0c:1d:a5:fe:69:

2c:69:24:78:1e:b3:a7:1c:71:62:ee:ca:c8:97:ac:17:5d:8a:

c2:f8:47:86:6e:2a:c4:56:31:95:d0:67:89:85:2b:f9:6c:a6:

5d:46:9d:0c:aa:82:e4:99:51:dd:70:b7:db:56:3d:61:e4:6a:

e1:5c:d6:f6:fe:3d:de:41:cc:07:ae:63:52:bf:53:53:f4:2b:

e9:c7:fd:b6:f7:82:5f:85:d2:41:18:db:81:b3:04:1c:c5:1f:

a4:80:6f:15:20:c9:de:0c:88:0a:1d:d6:66:55:e2:fc:48:c9:

29:26:69:e0

Note that some platforms (eg. Java’s JRE) use a specific default trust store (/etc/ssl/certs/java/cacerts on ubuntu).

We are going to need a server certificate. To be realistic, we will create a chain of 3 certificates, 2 CAs and a server. We could use a public CA (like Let’s Encrypt who deliver free certificates), but we would be challenged to prove that we own the domain name we want a certificate for, usually by hosting a file at a specific path on a public facing address. For simplicity sake, we will generate our own CA. The only difference is that our CA will not be in the system trust store so we will have to trust it explicitely by adding it to the user trust store or directly in the client.

First we create the root CA private key first. We will generate an RSA key of length 4096 bits. It will be stored in the rootCA.key file in PEM format (ascii)

openssl genrsa -out rootCA.key 4096

Then the associated certificate (self signed certificate, -x509 -new), unencrypted (-nodes), using our key (-key rootCA.key), valid for a year (-days 365), with a proper subject:

openssl req -out rootCA.crt -x509 -new -nodes -key rootCA.key -days 365 -subj '/CN=rootCA/O=LMT Corp'

Now we’ll create the intermediate CA private key just like we created the root:

openssl genrsa -out intermediateCA.key 4096

To sign it, we generate a CSR (certificate signing request)

openssl req -new -key intermediateCA.key -out intermediateCA.csr -subj '/CN=intermediateCA/O=LMT Corp' -addext 'basicConstraints = critical,CA:true'

and sign with the rootCA key

openssl x509 -req -in intermediateCA.csr -CA rootCA.crt -CAkey rootCA.key -CAcreateserial -out intermediateCA.crt -copy_extensions=copyall

And last, the server certificate:

openssl genrsa -out server.key 4096

CSR (with SAN):

openssl req -new -key server.key -out server.csr -subj '/CN=tls-server.local/O=LMT Corp' -addext 'subjectAltName=DNS:tls-server.local'

signed by the intermediate CA:

openssl x509 -req -in server.csr -CA intermediateCA.crt -CAkey intermediateCA.key -CAcreateserial -out server.crt -copy_extensions=copyall

Server side should be ok, let’s create a client CA and a client certificate. It’s really the same thing as the server except for one extension in the certificate, allowing its usage for client authentication:

openssl genrsa -out clientCA.key 4096

openssl req -out clientCA.crt -x509 -new -nodes -key clientCA.key -days 365 -subj '/CN=clientCA/O=LMT Corp'

openssl genrsa -out client.key 4096

openssl req -new -key client.key -out client.csr -subj '/CN=client' -addext 'extendedKeyUsage = clientAuth'

openssl x509 -req -in client.csr -CA clientCA.crt -CAkey clientCA.key -CAcreateserial -out client.crt -copy_extensions=copyall

All set! We can now start a server and test a connection. We will use openssl s_server for the server, and curl to test the connection.

openssl s_server -key server.key -cert server.crt -accept 8443 -www -cert_chain chain.crt -build_chain -CAfile clientCA.crt -Verify 10 -verify_return_error -tls1_3 -strict -ciphersuites TLS_CHACHA20_POLY1305_S

HA256

This creates a server listening on port 8443, using our server key/crt pair and our clientCA certificate for client authentication. The client certificate is mandatory (-Verify, -verify_return_error). This server only accepts tls 1.3 connections using the TLS_CHACHA20_POLY1305_S cipher. I’ve concatenated the rootCA.crt and intermediateCA.crt into a chain.crt file to establish the complete chain of trust. This server will send an http response with a summary of the tls connection if asked nicely.

To test it, we first need to add this line to our /etc/hosts file:

127.0.0.1 tls-server.local

This will allow us to call the server using a proper domain name, which is also declared in its certificate. Time to make a client call:

curl https://tls-server.local:8443 --cacert ./rootCA.crt --key ./client.key --cert ./client.crt

You should get an HTTP 200 status and a bunch of info.

Now that it works, let’s make it fail! For that we have to dive into the TLS handshake.

TLS handshake

I’m not going to explain every technical detail of the TLS protocol but focus on what can go wrong between the client and the server.

Before the TLS handshake, there is a TCP handshake of course. So if you can’t resolve the host name (DNS issue), can’t route (gateway issue) or timeout (firewall issue), the problem is in the network configuration and not in the TLS one.

Client Hello

The client sends its list of supported TLS versions and ciphers. The server checks if he supports one version and one cipher is this list (selecting the strongest cipher available on both sides). If the server can’t find a common ground of TLS version & cipher, it will send an error and close the connection.

For example if we try to use TLS 1.2 against our TLS 1.3 only server by using:

curl https://tls-server.local:8443 --cacert ./rootCA.crt --key ./client.key --cert ./client.crt --tls-max 1.2 -v

we will receive an error :

* TLSv1.0 (OUT), TLS header, Certificate Status (22):

* TLSv1.2 (OUT), TLS handshake, Client hello (1):

* TLSv1.2 (IN), TLS header, Unknown (21):

* TLSv1.2 (IN), TLS alert, protocol version (582):

curl: (35) error:0A00042E:SSL routines::tlsv1 alert protocol version

Same thing with the cipher:

curl https://tls-server.local:8443 --cacert ./rootCA.crt --key ./client.key --cert ./client.crt --tls13-ciphers TLS_AES_256_GCM_SHA384 -v

will return the generic error:

* TLSv1.0 (OUT), TLS header, Certificate Status (22):

* TLSv1.3 (OUT), TLS handshake, Client hello (1):

* TLSv1.2 (IN), TLS header, Unknown (21):

* TLSv1.3 (IN), TLS alert, handshake failure (552):

curl: (35) error:0A000410:SSL routines::sslv3 alert handshake failure

If the server and client share a common tls version and cipher, then the server will send its hello.

Server Hello, certificates, acceptable CAs

The server sends the selected TLS version and cipher, followed by :

- its certificate chain

- a request for a client certificate signed by a list of acceptable CAs

The client will first verify the server:

- check that the server certificate chain is valid (each certificate is signed by the previous one in the chain, none is expired), and that at least the root is trusted

- check that the server certificate matches the domain name we called

Since those checks are on the client side, they can be disabled (insecure or trust all mode).

For example if we don’t trust the root:

curl https://tls-server.local:8443 -v

the client fails with

* TLSv1.2 (OUT), TLS header, Unknown (21):

* TLSv1.3 (OUT), TLS alert, unknown CA (560):

* SSL certificate problem: self-signed certificate in certificate chain

and if we use a different server name than the one in the server certificate:

curl https://127.0.0.1:8443 --cacert ./rootCA.crt -v

* subjectAltName does not match 127.0.0.1

* SSL: no alternative certificate subject name matches target host name '127.0.0.1'

The client will by default check the domain name with the SAN or Subject alternative names declared in the server certificate. We only provided subjectAltName=DNS:tls-server.local when we created our server certificate, so it’s not valid for 127.0.0.1.

We can ignore those errors using -k, but we shouldn’t. These checks are here to ensure that you are indeed talking to the server you expect, and not someone else (man in the middle, someone intercepts your network traffic and tries to impersonate the target server, but this persone won’t have the proper certificate for the server).

Client certificate

The next step is for your client to select a certificate matching what the server requested. The server should send a list of CA, which you can see using openssl s_client:

openssl s_client -connect tls-server.local:8443

contains

Acceptable client certificate CA names

CN = clientCA, O = LMT Corp

At this point you will need your client key and certificate pair, you will send the certificate to the server (and a signature to prove you actually own the key).

If the client doesn’t provide any certificate, an invalid certificate (usually expired) or not matching the acceptable CAs, the server will reject it.

No cert:

* TLSv1.2 (IN), TLS header, Supplemental data (23):

* TLSv1.3 (IN), TLS alert, unknown (628):

* OpenSSL SSL_read: error:0A00045C:SSL routines::tlsv13 alert certificate required, errno 0

Unacceptable cert:

* TLSv1.2 (IN), TLS header, Supplemental data (23):

* TLSv1.3 (IN), TLS alert, unknown CA (560):

* OpenSSL SSL_read: error:0A000418:SSL routines::tlsv1 alert unknown ca, errno 0

Note that some clients (eg. java) will fail on the client side if they don’t find a valid client certificate in their keystore, some will try anyway to send whatever you specify or nothing at all.

As soon as you start receiving some HTTP response from the server, it means your handshake is successful. Congratulations!

TLDR - Troubleshooting

| Error | Usual source |

|---|

| The client get disconnected right after the client hello | the server couldn’t find a compatible TLS version/cipher in the list provided by the client. |

| The client closes the connection right after the server hello, complaining about an unknown CA or a self-signed certificate | your trust store doens’t contain the root CA of the server |

| The client closes the connection right after the server hello, complaining about an mismatched server name | the hostname you use to call the server doesn’t match the name declared in the certificate. Either the server is misconfigured, or you need to adapt your network configuration (/etc/hosts). Check the server certificate using openssl s_client to retrieve it, and openssl x509 to parse it. The hostname should match one of the SAN entries of the certificate |

| The client aborts the handshake after the server hello | the client is strict and fails to find a valid client certificate to send to the server. Check that your keystore contains your key, your trust store your certificate, and depending on the language you may need to trust the CA of the certificate too. |

| The server closes the connection requesting a client certificate | you didn’t send a client certificate. check that you have valid a key/certificate pair in your trust store/key store, matching the server Acceptable CAs field. |

| The server closes the connection complaining that the CA is unknown | the client certificate you presented does not match the expected CA. Check your certificate CA against the list of Acceptable CAs provided by the server |